Understanding Writing Behaviour Through Icek Ajzen's 'Theory of Planned Behaviour'

Reflective exploration of motivation, intention, and self-regulation in academic writing

During my PhD, I came across the Theory of Planned Behaviour (TPB) by Icek Ajzen (1991), primarily while evaluating physical activity interventions. I was looking at how motivation and intention predict whether someone would engage in exercise. But I began to wonder—can this same theory help explain other types of human behaviour, such as writing? As someone who doesn’t naturally identify as a prolific writer—more an orator who relies on speech-to-text tools to articulate thoughts—I’ve long been interested in how writing behaviour develops, especially within academic contexts.

In a previous article, I briefly touched on the question: Is writing a psychological act? This essay builds on that idea by exploring how TPB can help us understand the act of writing, particularly in academic settings. Writing is not just a mechanical process; it’s a complex cognitive and behavioural activity, shaped by psychological, social, and environmental factors. For students and researchers, writing is often a requirement—research papers, essays, and journal articles are core outputs. But how and why we engage with writing is less straightforward, and this is where TPB offers insight.

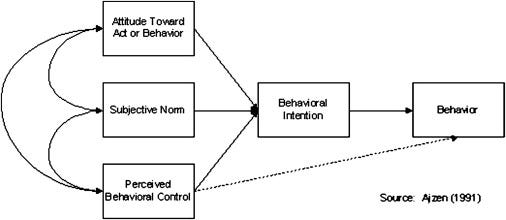

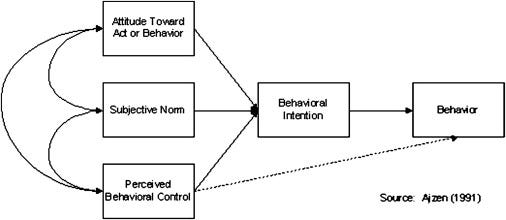

Ajzen’s TPB suggests that behaviour is primarily driven by intention, which in turn is influenced by three psychological constructs: attitude, subjective norms, and perceived behavioural control.

Firstly, attitude refers to an individual's evaluation of the behaviour. If someone believes writing is meaningful—perhaps it helps them express creativity, organise their thoughts, or succeed academically—they’re more likely to have a positive attitude and therefore intend to write more often. Research by Wolters et al. (2017) supports this, showing that favourable attitudes predict writing frequency and persistence. In contrast, if writing feels overwhelming, tedious, or anxiety-inducing, it can become a barrier.

Secondly, subjective norms involve perceived social pressure. In academic environments, students often feel the pressure to write because everyone around them is writing—supervisors expect it, peers are submitting papers, and deadlines loom. This sense of shared effort creates implicit social expectations. When writers believe that significant others value and expect good writing, they’re more likely to internalise those norms. Research by Limpo and Alves (2017) found that perceived social norms strongly contribute to students’ ability to self-regulate their writing.

The third component, perceived behavioural control, relates to one’s confidence and perceived ability to complete the task. This includes time management, writing skills, and access to resources. If a person feels capable and supported, they are more likely to follow through on their intention to write. Ajzen (2002) further explains that when perceived control is high, the gap between intention and behaviour tends to close. In other words, believing “I can do this” significantly boosts the likelihood of actually doing it.

What makes TPB particularly valuable is that it doesn’t just describe behaviour; it provides a framework for interventions. For example, writing workshops can enhance perceived control by improving skills, while peer support groups can boost positive subjective norms. Educators can therefore use this model to help students and academics alike develop stronger, more sustainable writing habits.

In conclusion, the Theory of Planned Behaviour offers a robust psychological framework for understanding writing behaviour. By examining the roles of attitude, social expectations, and perceived control, we gain insight into why people write—or avoid writing—and how to support them in the process. For someone like me, who naturally gravitates toward speech and reflection, understanding these psychological mechanisms has been essential in building confidence and consistency in writing.

References

Ajzen, I. (1991). The theory of planned behavior. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 50(2), 179–211. https://doi.org/10.1016/0749-5978(91)90020-T

Ajzen, I. (2002). Perceived behavioral control, self‐efficacy, locus of control, and the theory of planned behavior. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 32(4), 665–683. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1559-1816.2002.tb00236.x

Limpo, T., & Alves, R. A. (2017). Modeling writing self-efficacy and writing self-regulation as predictors of writing performance: Effects of grade level. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 49, 36–46. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cedpsych.2016.11.004

Wolters, C. A., Benzon, M. B., & Arroyo-Giner, C. A. (2017). Assessing academic self-regulated learning in context: The Research on Learning and Development of Self-Regulation (RoLDS) questionnaire. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 51, 39–50. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cedpsych.2017.05.002